AIP-Ohio University Programme | We’re not in the news business, we’re in the connection business

“Your product is not news, your product is connectivity.”

Prof Bill Reader kicked off the first week of the AIP trip to Ohio emphasising to the South African publishers that “an effective community journalism operation holds its community together with reliability, caring (‘tough love’), and trust.

Prof Reader’s presentation showed how community journalism was the foundation of American journalism. “A community arrived as a real place when it got its own newspaper.” News was collected from main centres, the larger cities, then local commentary was added. What was interesting is that most of the owners were printers first, not journalists and produced newspapers on the side.

By the mid-18th Century, most publishers produced patriotic papers, taking the point of view of the people, while some were loyalists who followed the King of England. Soon however newspapers in America began to follow ideologies and cultures.

“Wherever a town sprang up, there was a printer, and a newspaper, as the country expanded to the west, the land was cleared by slaves, built by poor immigrants, stolen from first people and news media moved with frontier,” said Reader.

By the mid-1800s, nearly every small town and frontier territory had at least one weekly newspaper, he reported. Then in 1844, the invention of the telegraph led to the Associated Press being set up by New York City newspapers so they could share the costs of getting news about the U.S. invasion of Mexico. The wire service expanded to link news media across the nation, bringing neutral and simple facts with a national slant so that the competing newspapers could use the copy.

This was the beginning of the idea of neutrality where different views had to be catered for by facts and objectivity became a business decision.

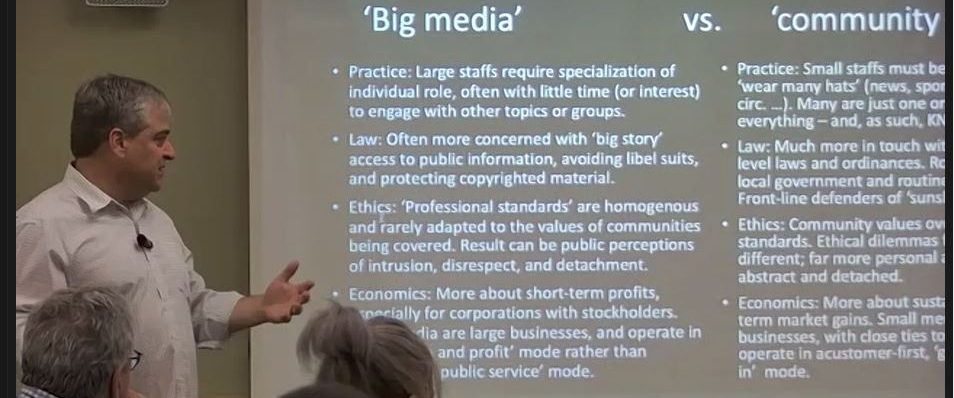

But “detached” journalism in the U.S. led to a “disconnect’ between publishers and audiences.

“From the late 1980s, many in the U.S. media business vowed to ‘reconnect’ news

media with their audiences. This resulted in initiatives such as civic journalism, citizen journalism, and solutions journalism”.

To be sustainable, and to thrive, community journalism models need to have “multiple delivery modes (based on audience preferences), diversified product/service offerings, and flexible (‘opportunistic’) work streams”.

Prof Reader explained how rural and far-flung communities are facing a news drought because publishers are based in the larger towns and journalists working for these operations are seldom seen in the remote areas.

“It helps to know that we’re not alone,” said Xenor’s Shirley Govender, observing that so many of the challenges faced by South African publishers are exactly the same as those confronting US publishers. We have a great deal to learn from each other.

It was pointed out by Professor Reader that effective community journalism (CJ) holds people together, it is built on caring and an ethic involving trust. But he also warned that CJ can include tough love, where the reports can reveal negative things about the area.

“By 2015, 85% of newspapers in the U.S. were community papers which is 60% of total print circulation and even after COVID-19 the community papers are still the dominant part of the publishing sector, and yet everyone focuses on the national papers,” he said.

“There is a local news crisis in the U.S., and flagging advertising and subscriptions are major drivers, especially in economics-strapped communities.”

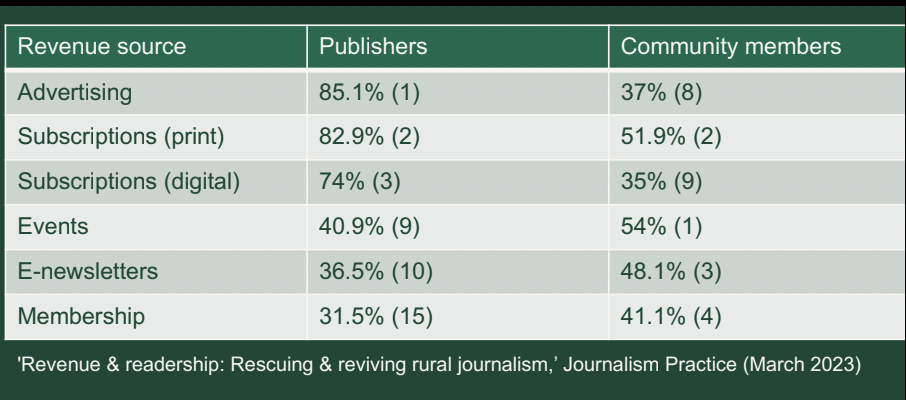

A recent newspaper analysis led by University of Kansas researcher Teri Finneman revealed that there is a significant divide between what publishers and community members thought about revenue sources. For example, publishers preferred traditional advertising and paid subscriptions for both print and online, whereas readers said they would pay for events, print subscriptions, e-newsletters and even memberships.

The lunch break saw a minor South African invasion of the local KFC franchise, as AIP publishers compared the size and juiciness of local portions.

After lunch, AIP member publishers Andile Nomabhunga (The Informer) and Anetta Magxaba (Dizindaba) shared how deeply their relationship with their communities run, and the creative strategies they have used to balance their business needs and their community service.

Nomabhunga explained how he had decided to launch a new Digital Television project that was beginning to pay off. Magxaba said she and her partner had developed a strategy when it came to selling advertising, focusing on the isiXhosa language.

“We tell the advertisers, it’s your choice to advertise in your language, but now you have to do it in Xhosa,” she explained.

But the reality of working as a publisher in South Africa has seen her newspaper move from a spacious office to her home as economic headwinds and costs ramped up. There have been surprising silver linings, however.

“The pandemic was our best year ever in the history of the newspaper,” she said.

“We made close to a million rand mostly on government ads, that’s why we went back to a weekly.”

Prof Mark Turner’s presentation engaged the visitors in a deep, wide-ranging and animated discussion about community journalism business models.

He asked a simple question. Is Journalism a business, a public service, a mix of the two, or something else entirely.

His presentation clearly mapped out the different business models being used by US community media. He challenged participants to debate whether they are primarily businesses or if they exist to serve the community.

“We should not be apologetic about the fact that we are running businesses,” the South African publishers insisted. We can’t serve our communities unless we can pay the bills.

Prof Turner suggested that “we care about your community and this is why you should continue to support us,” is a message we could be giving potential advertisers and partners.

“I think you make money off your mission,” he said. “You just have to find the right streams.”

Most publishers agreed that publishing was a mix of public service and business, although Professor Read said he believed journalism itself was separate from business. The art and science of writing news should be done away from deciding whether it was an online, print or other form of business model.

PS: Apologies to those who struggled with the live stream today. Technical glitches had the South African MacGyvers stretching their creativity to work out ways of getting the audio system working.